Currency

EURVoltage

220VWater

GoodDialing

+590Arrival by boat Entry formalities

Clearance formalities for entry and exit from the islands of the French Antilles is now mandatory for all pleasure boat, for personal or professional use, arriving or departing by sea

Clearance

The procedure is free and can be done online here, or in person at one of the approved points. This electronic procedure is very convenient, but most other countries will request a printed and stamped EXIT clearance document. So you will need to print your EXIT clearance in order to get it stamped in one of the approved points listed in the above document, it can be a local shop or marina. This approved points of clearance also provide public computer where you can fill and print your document for 3 to 5€.

Visa & Immigration

Official website for visas to France

Other ressources

Noonsite.com maintains an updated worldwide database of formalities for pleasure crafts. Click here for more details.

Weather & Navigation

Composed of several islands, Guadeloupe is an enchanting archipelago divided into two main islands, Grande-Terre, Basse-Terre, and several smaller islands. Inland you’ll find dramatic landscapes such as La Soufrière volcano, an area also known for its natural hot springs. The Cousteau Reserve, named after the famed ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau is a protected area, and diving near Pigeon Island is a unique experience.

While sailing in Guadeloupe be cautious of the interaction between the trade winds and the island’s high volcanic peaks, particularly on the Basse-Terre side. These mountains create localised wind acceleration zones, especially near the Pointe des Châteaux and the narrow straits between the islands.

Sailing itineraries in Guadeloupe

A brief maritime history of Guadeloupe

Long before European explorers, the island was home to indigenous peoples with their own rich cultures and traditions. The earliest known inhabitants, the Arawaks, arrived around 300 AD. They were peaceful agriculturalists who fished and cultivated crops like cassava, maize, and sweet potatoes. Their pottery and artifacts, some of which have been uncovered in archaeological digs, give us a glimpse into their daily life and the serene existence they carved out on the island.

But the Arawaks wouldn’t remain alone on the island for long. Around the 9th century, the Kalinago (often referred to as Caribs by European colonisers) migrated from South America. Known for their warrior culture, the Kalinago quickly established dominance in the Lesser Antilles, including Guadeloupe. They were fierce defenders of their territories and often engaged in raids against neighbouring islands. The Kalinago were skilled navigators and seafarers, traveling in large dugout canoes across the Caribbean Sea. They named the island “Karukera,” or “Island of Beautiful Waters”.

For centuries, the Kalinago thrived, living in coastal villages and relying on fishing, hunting, and farming to sustain their communities. They developed a robust trade network with other islands, exchanging goods like tobacco, cotton, and ceramics. Despite their warlike reputation, their society was organised and deeply spiritual. Rituals, dances, and festivals marked important events in their lives, and their respect for nature was woven into their way of life.

Christopher Columbus landed in 1493 during his second voyage to the New World, he renamed the island “Guadalupe” after the Royal Monastery of Santa María de Guadalupe in Spain.

For nearly a century after Columbus’s visit, Guadeloupe remained under Kalinago control, as they managed to fend off any European settlement attempts. The Kalinago were adept at guerrilla warfare, utilising the island’s dense forests and rugged terrain to their advantage. The islands were remote enough that serious attempts to colonise them weren’t sustained until the French colonisation kicked off in 1635. The Kalinago fought valiantly, trying to hold onto their land, but diseases brought by Europeans, combined with relentless battles, devastated their numbers. Over time, the French solidified their control, and Guadeloupe became an integral part of France’s growing colonial empire.

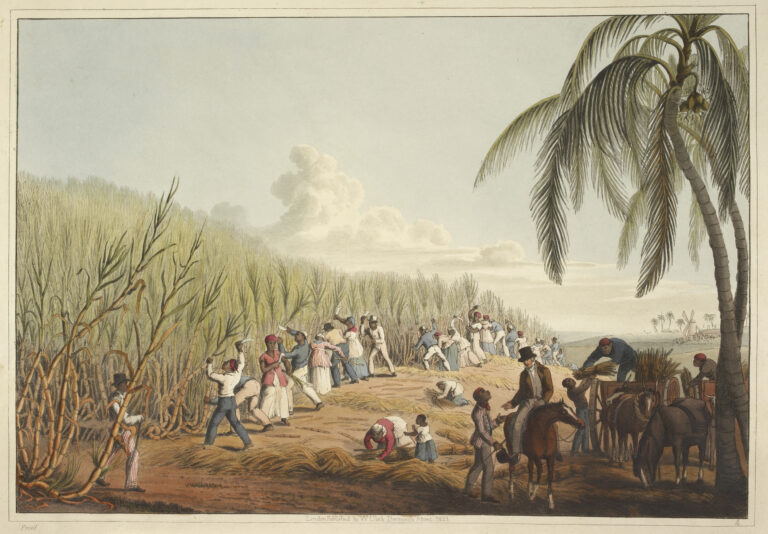

The plantation economy took root in the 17th century, driven largely by sugarcane, which quickly turned into the island’s cash crop. But the sweetness of sugar came with a dark reality—slavery. Thousands of Africans were forcibly brought to Guadeloupe. Yet, their resilience became the culture, a thread of survival that has shaped the island into what it is today. On May 22, 1848, slavery was finally abolished, putting an end to a dark period in history. The legacy of slavery is still deeply felt today, woven into the island’s Creole culture, language, and identity.